Director: Margarethe von Trotta

Camera: Franz Rath

Editing: Dagmar Hirtz

Germany in Autumn

Sister, it's war!

I saw "The Leaden Times" when I was 15 through our school film club in the studio stage of the Rundkino Dresden.

I've been having a hard time with "The Leaden Time" by filmmaker Margarethe von Trotta for a few days. I was happy at the weekend to finally find the book "The Leaden Time and Other Film Texts" on my bookshelf, which was published in 1988 by the East German Henschel Verlag and which - I suspect - was published in the East German at the same time as her film "Rosa Luxemburg".

Margarethe von Trotta also came to Dresden for the cinema premiere, where - out of fear of what was going on in the country - the premiere was moved from the large hall of the Rundkino (at the time the largest cinema in Dresden with 1,017 seats) to the studio stage of the Rundkino (capacity 156 seats). That was in the spring/early summer of 1988, a few months after the Berlin demonstration to honor Rosa Luxemburg/Karl Liebknecht, the protest and the subsequent arrests because of the freedom of dissidents. Freedom did not prevail.

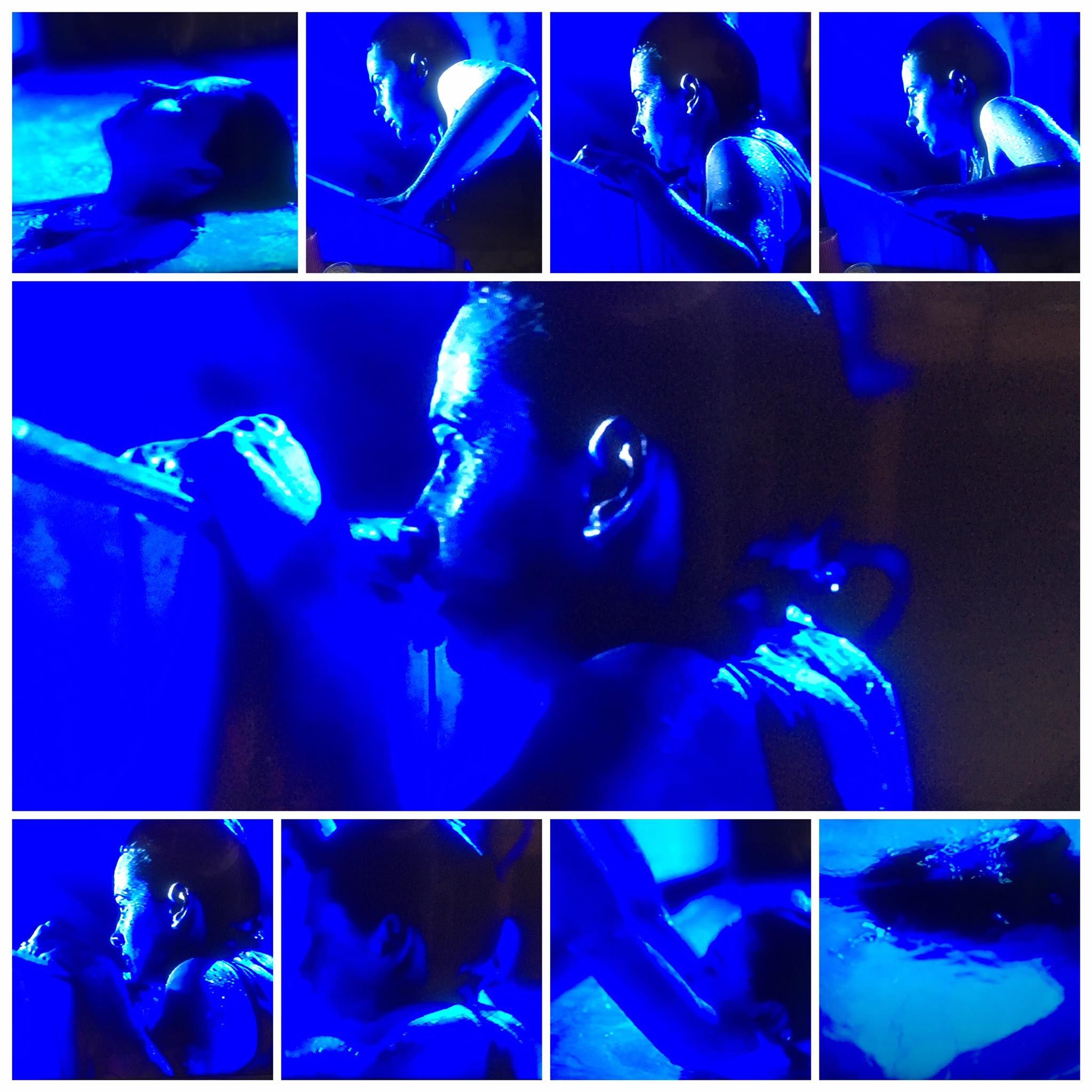

When I was 15, I was able to see "The Leaden Time" through our school film club in the studio stage of the Rundkino in 1982 and was electrified for a long time by the intensity of the personal truths that the Ensslin sisters sometimes shouted out, memorably embodied in the film by Barbara Sukowa and Jutta Lampe.

"Sister, it's war!" is still what shoots into my head today when I hear verbal radicalism or, in my own words, find myself exposed to a totalization of language.

The RAF terrorist Marianne shouts this at her sister Juliane, the women's rights activist, when she shows up at Juliane's apartment with her friends at night and makes coffee, having come straight from a Palestinian training camp. "That you can still stand it here," Marianne says to her sister, and immediately afterwards: "I'll set the coffee table first."

In "The Leaden Time", Margarethe von Trotta tells the story of the two Ensslin sisters, Christiane and Gudrun, four years after the death of Gudrun Ensslin in the high-security wing of Stammheim - after Gudrun Ensslin's funeral, Christiane spent several days explaining the intense and ambivalent sisters' relationship to the filmmaker.

The sisters were born in 1946 and 1947 in a parish household and grew up in the "leaden times" of the post-war period of the 1950s. "I have also described myself, my feeling of having lived in the 1950s as if under a leaden sky, under a lead cap of silence. You could sense that there was something in the past, in the war, but we were not informed about it. We wanted to break out of this ignorance. That was also a trigger for the first RAF generation to resort to violence," Margarethe von Trotta said in an interview. "A lot of what we thought back then I can hardly understand today. We were blinded in some ways, which is also due to the fact that after 1945 there was no instruction in political and democratic thinking in schools.

That is why 1968 was a shock that made us equate rebellion with political action.

The history of the RAF is a tragic one: the first generation of terrorists in particular not only murdered, but also eliminated themselves and isolated themselves from the world, whether by killing themselves in Stammheim or by spending decades in prison. They destroyed the lives of others and wasted their own, out of a misguided rebellion."

Margarethe von Trotta

While the younger Marianne plays the cello dreamily and sensitively and recites Rilke, her sister Juliane is a rebellious teenager who rebels against her patriarchal father at an early age and later becomes editor of a feminist magazine.

“One generation earlier and you would have become BDM”

Marianne joins the RAF and goes underground. Her son Jan is eventually given to Juliane by his father Werner - Werner later commits suicide. After Marianne is imprisoned, her sister Juliane is her only point of reference - but even during visits to the prison, their different perspectives collide. Juliane was asked by her editor to write about her sister. The editors, in turn, accuse her of marketing her story for the pig system, like the Springer press, by explaining the political activities based on her personal history. Juliane responds: "One generation earlier and you would have become BDM." Marianne gives her a resounding slap in the face - to the satisfaction of the middle-aged guards, who grin broadly.

What Remains

"I was interested in the continuity of German history in the succession of generations. First, people allow themselves to be seduced by National Socialism. Their children blame their parents for this, but then allow themselves to be seduced by an ideology again, even to the point of murder. I didn't want to condemn, I wanted to understand how it came to this.

The public behaved differently back then, the fronts were hardened.

The hysteria was so great on the part of the police apparatus that we thought there would soon be a new police state. Extreme reactions on both sides.

The Nazi era was not that long ago in 1968, there were judges and politicians with a Nazi past who had integrated into post-war Germany. Back then, we didn't really believe that Germany was capable of democracy. There is another line that continues to this day: Peter-Jürgen Boock says in the "Spiegel" that, even with regard to the decades-long silence of the RAF, the RAF people were the children of their parents. This is why he recently became very angry with them at the grave of Gudrun Ensslin and Andreas Baader. "The susceptibility of the Germans, which always results in them acting radically and murderously, also corresponds to the equally radical repression of our history. This was similar after the 1970s as it was in the 1950s." (Margarethe von Trotta)